JAMIE O'HARA LAURENS INTERVIEWS MICHAEL ODOM ON SELENE

Selene: In Poems by Michael Odom

MICHAEL ODOM'S LUNAR DISQUIET: SELENE

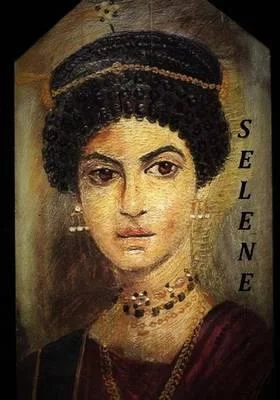

Michael Odom’s Selene is a raw collection, the centerpiece of which is the mythic version of a vague and distant figure in troublesome human form. Selene was the goddess of the moon, for whom Cleopatra’s daughter was named, and the collection focuses primarily on the observation of a contemporary incarnation of this persona. The poems at times move in a cohesive arc following the speaker’s relationship to Selene. At other times they follow divergent threads and arms in an environment that, while dystopian, is rich with sound and imagery. The majority of the collection takes place in the home of the speaker and Selene, where the persona, rather than spoken for or spoken through, is viewed from the outside: the speaker grapples with a range of emotions from lust to bitterness, until an untimely end concludes their communion.

In the midst of the dance between two unhappy players, Odom takes on materialism, credit, debt, illness, and the warmongering of contemporary culture. In the background pollution, addiction, traffic, and the threat of sickness lurk:

War & Plague & Death ride by

Outside in their thundering city.

The speaker is openly critical of the hunger for power and material goods, notably Selene’s, as well as of her her cronies, who seem blinded by the pursuit of conventional success. Upon Selene’s arrival, there is a mixed message. There are moments when we encounter macabre imagery of devotion:

She, my hag, will feed me her hard-bean soup

If I trim her toenails, store her clippings

For art, and coolly blow on her bunions

At the same time, their home is a shelter, at least temporarily, from the ills of the outside world:

Our home is nothing fire can burn

Or poverty dissolve.

The collection opens with a clutch of poems that call into question the contemporary assumptions and unconscious rituals of manhood. The ending of this untitled sonnet suggests at once a portable source of light and life, and a male child who has succumbed.

The simple strength of men who never know,

Their muscle-coats, their steel, their robotic wars,

Their Scantron lives lesson-planned in their brains […]

Big man boasts… I know a boy much smaller

Who carries in his pocket a collapsed sun.

The poem’s volta remains hopeful—“I know a boy” suggests that exceptions like the named boy and the speaker himself remain.

Financial hardship infuses the collection with a sense of lack, the blame for which changes hands. Selene at one time dreams “last night the rent got paid.” The poem “Hours late…” ends with a line that strikes at the heart of the collection’s core theme:

With longing enough to max a card

Odom recently wrote to me from sunny California to answer a few questions on the songs, diatribes, and dances of Selene.

JL: Sociologists and psychologists are telling us how the journey toward vulnerability, particularly masculine vulnerability, is a highly necessary one, connected to courage and authenticity. In Selene, the speaker lays bare frustrations and fears on notions of success and failure. What role does vulnerability, particularly as a male writer, play for your speaker and in your process?

MO: Part of the failure of the couple in the book is Selene’s very conscious girding herself against him for the battle with world outside them. The speaker, on the other hand, lacks or removes armor and is wounded where exposed. Selene may find courage, but not authenticity. The speaker may find increasing, tragic authenticity, but not at all courage.

I think they fail each other and themselves. The speaker is failing to adjust to the loss of an abstraction he loves. He is mourning that loss and licking the wounds as he fails to achieve love for the individual woman. His only hope was to love the abstraction as expressed in the human body, not as conceived in the human mind.

For the artist, the lack of vulnerability means death. If I am not exposed enough to see into the very core of my being, my work will be abstract, assumed, and dull for lack of core being. Core being is the best material for a maker.

JL: When Selene appears, the speaker engages a tough counterpart in a toxic dance. Her appearance in the collection is mysterious, sudden, her arrival barely anticipated. She announces her first act of love: Now for my revenge. It seems that when she arrives in the text, the speaker is already married to her—almost as if the marriage is haphazard, accidental. What brings her into being?

MO: There is a hint of courtship and a nuptials poem, but you are right. She appears magically, suddenly, unexpectedly, and abstractly. She hardly exists until they are married. She is not his mate until she is gone.

Like all goddesses who are real, she preexists and is exclusive from her lover. Like all goddesses real or no, great need brought her into being. His need is desperate. He is incapable of doing anything about it himself, with or without her.

The need, of course, is the biological need for a mate. To that purpose, nature gave us the need for beauty, the worship of bodies, (from insects & birds to us) to bring us together, and the need for love, the continued fascination with our specific others.

JL: Many of the poems sing, in that they are loose or partial sonnets, pantoums, or songs. Do you have a favorite form to work from?

MO: The function of verse is transcendence. That is why, when the earliest civilizations created an art of language, they did so to speak of gods, the culture’s stories and history, and, later, love (thank you, Sappho). To raise speech above the ordinary, they made it rhythmic, chant-like, musical, and often sought new or careful diction for effect.

For many, verse is just prose with wide margins. In reality, verse is necessarily metrical, the term ‘metrical’ refers to an enormous range of possibilities, and it exists for important reasons.

Much of the book is an attempt to bring classical hendecasyllabic, Sapphic, elegiac, and other meters into English. Catullus (I am told by some who know this kind of thing) used a broad range or meters, none of which will work in English. They are falling rhythms and only analogously accentual. I experiment with substitutions and creating new English forms with combinations of different meters he used. I find elegiac meter really beautiful, but I chicken out over and over when it comes to singing it loud and proud: like with sonnets and iambic or rhymed forms, I look for subtle music that others don’t recognize right off. Probably cowardice….

Music is key to verse so it is key to the creation of verse. It is what separates verse from prose and speech. I usually have music playing when I write. For many years, it was Faure’s Requiem, and later his & Chopin’s Nocturnes. These days, Eric Whitacre or Bach. And my son has me listening to some contemporary composers of ambient music. I will often very consciously try to let the music be a map of my poem. When the music is louder, allegro, or passionate, then transitions in tempo or dynamics, I will choose diction or metrical substitutions in my form to follow.

JL: What led you to choose the persona of Selene? Does she have a particular relationship to the mythological figure, or to Cleopatra’s daughter?

MO: All of the above and a few more. The goddess of the moon is a symbol of feminine beauty and power, which of course is 99% delusion. Woman as goddess is necessarily frustrating and frustrated, especially to the secular. The understanding of love as a kind of worship (from Stephen Mitchell, prayer is a quality of attention; for most, when they love they will pay close attention for the first time and that attention will wane) is a peek behind the mask of a religious phenomenon. If there is no god or goddess, then why do we worship?

JL: If worship is failing us, how does artistic expression take its place?

MO: I used to agree that emotion in a poem is manipulative, telling readers what they should feel. But in music? What would be the effect of a composer who made their works flat thinking the audience should deduce feeling? In art, the desperate attempt to remove the sentimental or manipulative leads to monochromatic painting.

A lot of what artists do is signal to the audience by reacting to what is happening. Like when a small child falls and looks up to its mother. If the mother reacts with fear and horror, the child senses something terrible has happened and feels that fear too.

JL: If the speaker in Selene could predict the future, what might he warn us of?

MO: The loss of our humanity, human feeling, human thought, human creation, as we adjust our selves to suit a world that would really rather have robots.

JL: So, regardless of the slings and arrows, you’d rather we feel the full palette of human experience than be deadened to it. Does the material gain the speaker is critical of participate in this deadening?

MO: Yes, but it is flattering to the materialists to call our spiritual losses material gain when most people manage only economic stasis or decline. Selene seems to climb, possibly, but not to any level that she could not be knocked off of with one economic reversal. We are taught what we do as employees or prospective employees matters. Our human needs, our animal plus intellectual needs, are side issues unworthy of great time or sacrifice.

Selene reveals many facets of the underbelly of gain in our culture visible in the intimacy of a couple. While at turns it could be more tautly streamlined, it is a danse macabre of resistance well worth the read.

Jamie O’Hara Laurens writes poetry and nonfiction. Her first collection, Medaeum, is available from Ping Pong Free Press. She lives in Brooklyn, and teaches in Manhattan.

Michael Odom is the author of Boredom, Vice and Poverty and the chapbook Strutting, Attracting, Snapping. He is seeking a publisher for his translations from Catalan of poems by Joan Maragall and Lluís Roda. His poetry has been published in the literary journals, Clean Well-Lighted Place, The Henniker Review, In Posse, Pucker up, Watershed, and others, as well as two anthologies, Between the Leaves and Ritual Sex. Between 1989 until recently, he was a bookseller, Manager, and Buyer for both independent and chain bookstores. If you shopped for poetry at the Tower Books in Chico, CA, or Manhattan, in the early 90’s, you browsed the titles Michael Odom selected to have on sale in that store. The same is true in the final 7 years of A Clean Well-Lighted Place for Books in San Francisco (which went out of business before the unrelated journal of similar title began) and Windows on the World in the Sierra foothills. As a single father with bookstores closing all around, Michael Odom pursued and recently received his MFA in Poetry from New England College. His latest book, Selene: In Poems is available on Amazon.com.